Your Cart is Empty

Orders can take up to 3 weeks at times.

(Preparation, Perseverance, & Perspiration)

The sun was starting to set behind me and I marveled at the fifty or so head of elk grazing about three quarters of a mile from me, their bodies glistening like beacons in the fading light.

I was calling coyotes on what would be my last stand of the day. I had set up on a small ridge in some sagebrush that gave me a good view to my left and out to my front. The ridge I was on proceeded in an arching curve to my right and ended at a higher point about ½ mile from where I set up. The only thing that bothered me was a tall patch of sagebrush that ran off to my right for about 250 yards, which of course was the direction a very slight breeze was drifting towards. (But no stand is perfect when it comes to calling coyotes.) What had brought me to this spot was I had heard coyotes howling from the distant canyons about an hour earlier and with the elk in the area I felt this would be a productive stand. But I had thought each of the previous 7 stands were equally good in their own way and would have coyotes tripping over themselves to get to me, but to no avail. However I still had high expectations for this stand and would hopefully see at least one coyote before the day ended (hence Perseverance ) . . . . .

Over the last several years I have gotten back into calling coyotes from when I used to do it 30 years ago. Gone though are the days of using mouth calls that would freeze up on you, shooting sticks you held together with rubber bands, clothing that was guaranteed to leave you wet and ammunition that would occasionally go “click” when you pulled the trigger. But even with today’s advancements in equipment used for predator calling, there’s one thing which hasn’t changed: a coyote’s cunning nature. If anything they have become even more challenging to call.

One of the keys to being successful with your coyote calling is just how well you begin your “Preparation”. This would involve knowing the habits of coyotes. Using the right equipment for the task then knowing how to use it, and above all else practice with it A personal friend of mine who is owner of one of the leading electronic predator calls companies on the market told me they frequently have calls and transmitters sent back to them which are believed to be faulty. What they find is that the calls are actually fine; it’s just that the owners didn’t know how to operate them properly. Knowing your equipment and how to use it will certainly tip the odds in your favor of being a successful hunter. Another aspectI stress to hunters is the importance of being familiar with their rifles. It may seem basic, yet I see so many people who never practice. A coyote is not a very big target. Once you get that fur off them their kill zone is about the size of a 6” saucer plate. Add to that the conditions which you may have to be shooting in, such as blowing snow and extreme cold, and it becomes even more difficult to shoot accurately. In addition, rifles being placed in and out of vehicles have been known to have the scopes knocked out of alignment. It’s frustrating if you spend a considerable amount of time trying to call in a coyote only to miss the shot, or several, due to a scope that got bumped. So periodically through the calling season check your scope and practice your marksmanship.

Now all the preparation in the world can be done, but things can and will go awry when it comes to calling coyotes. That’s what makes it challenging---you never know what may happen. I had one stand this season that looked like it would be a good one. The downside was the wind had picked up to about 25 mph with a wet snow blowing in sideways. The temperature was about 20 deg. I knew the wind chill factor was bone chilling. However, I still wanted to try this stand before I called it quits due to the wind. I found a good vantage point on a knoll and put the call out in front of me about 25 yds. I found myself a large clump of sagebrush to sit in. My .223 bolt action rifle was on its bipod and ready for action. I could see for miles from this position. I started my calling and 4 minutes into the sequence I saw a coyote standing about 100 yds in front of me on a small ridge, as usual it had appeared out of nowhere. I eased my rifle up to my shoulder and centered the crosshairs behind its shoulder. Upon squeezing the trigger the rifle went “Click”. The coyote looked in my direction, but was still trying to figure where his meal was. I thought the shell might have been a dud, so I loaded another round while the coyote was moving to a new spot. When he stopped the trigger was again squeezed, but again the rifle went “Click”. The coyote moved, and I again put another round into the chamber. I thought third time had to be a charm, so when the coyote stopped about 60 yds away I squeezed the trigger. . . . . “Click.” I knew then that my rifles firing pin was froze up due to the moisture and extreme cold. That was one lucky coyote that day.

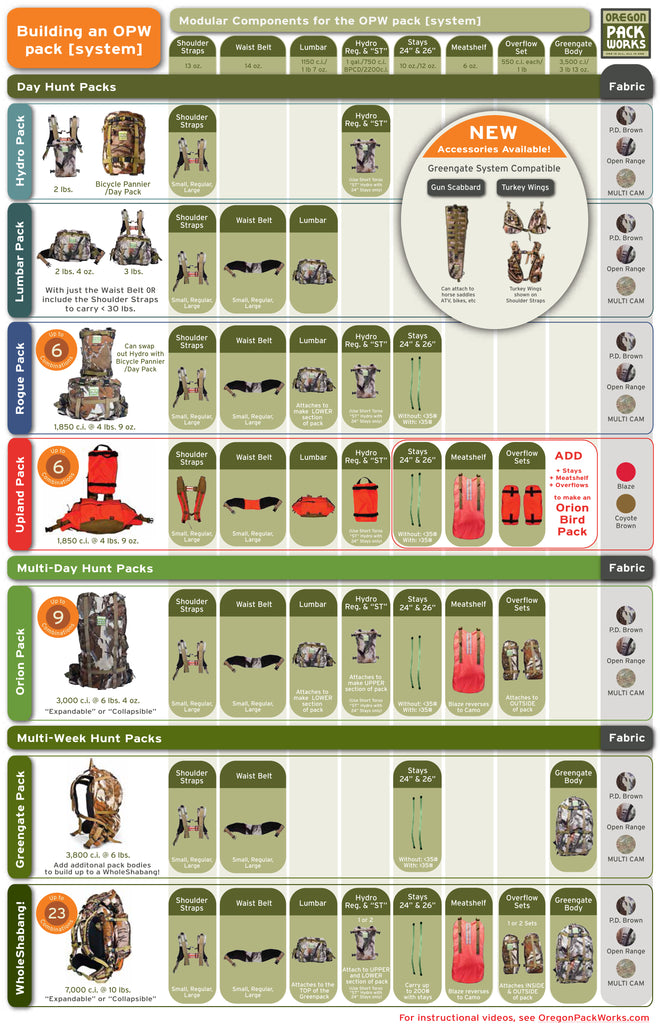

When I leave my truck and walk to a stand I have the following essential equipment with me. My rifle, electronic call, rifles bipod, sitting stool, and of course my Oregon Pack. All this equipment is carried by my Oregon Pack in the Rogue configuration with the meat shelf (aka “coyote carrier”) attached. I have found with the increased popularity of predator calling that call-wise coyotes have become weary of stands within close proximity to traveled roads. This is where the “Perspiration” factor comes in. I will strap my Oregon Pack on and head for distant hills that I know aren’t being called. This means fewer stands are called in a day, but I have found my success rate is higher. The use of my Oregon pack makes this an easy chore. Case in point: this winter I walked to a hill about ¾ mile from the road and set up. The hillside was a steep one, but it afforded me an excellent view off towards the sagebrush flats out in front of me. About 8 minutes into the call I heard a slight sound back behind me up in the rim and noticed a raven flare up into the air. About 45 seconds later a coyote suddenly appeared from off the hillside to my right and was almost on top of the call. I managed to make the shot just as the coyote decided he needed to be somewhere else. I continued my calling sequence and about 6 minutes later a coyote came trotting across the flats in front of me. When he stopped less than 50 yds from me I made that shot. If it weren’t for my Oregon Pack I would have struggled carrying two coyotes back to the truck over ¾ mile distance. But in this case I simply loaded the coyotes onto the pack and strapped them down with the meat shelf. The walk back to the truck was a simple task.

The last thing I have found with calling coyotes is to be “Perseverant”. I’ve called on days that I thought would be good due to weather conditions, but turned out I wouldn’t get a single response. Yet at other times things fell into place just when it seemed like nothing was working, which brings me back to the opening of this article. After having called 7 stands previously without seeing a single coyote I was determined to give it one more try. The elk were off in the distant grazing and my call was out in front of me about 25 yds, when I started my calling sequence. I had been calling for 13 minutes and was already thinking about shutting things down when I saw a coyote walking through the sagebrush on the hillside to my right. I estimated it was about 500 yds away. As I watched it sat down looking in my direction. It seemed disinterested in what I was offering for a meal, but after sitting there for several minutes it started trotting down off the hill headed right for that large patch of sagebrush on my downwind side. My rifle was up and at the first opportunity that I could get my crosshairs on its shoulder I planned to fire. If it got my scent before I could fire, I knew I wouldn’t have another chance. As the coyote was slipping through the sagebrush I got it to stop in an opening at about 175 yards and was able to make the shot. As my rifles shot was echoing off the hills I looked back up where this coyote had originally appeared and there were two more coyotes. But with the rifles shot they had started to run up the hill away from me. I got my call back into action and the coyotes stopped. One of them was hesitant to make any move, but the other one started down the hill towards the same patch of sagebrush the first coyote had went into. However I noticed it was going to stay out further and try to pick up my wind. When the coyote entered into the sagebrush I lost sight of it, but within a couple seconds it was running out of the sagebrush and back up the hill from where it came. I managed to get it to pause just for a second and was able to drop it at a distance of 276 yds. I immediately checked off to my left and there was another coyote that had been working its way in, but at the shot it too turned and started running back out. With some quick coaxing from my voice I got it to pause at a distance of about 250 yards and dropped it too. By this time 34 minutes had elapsed since I started the call. I figured I might give the stand another 10 minutes or so and see if anything else were to happen. With a fresh magazine inserted into my rifle I was ready. Eight minutes later a large coyote suddenly appeared about 200 yards out in front of me and headed right towards my position. When he paused about 80 yards away I dropped him. I now had 4 coyotes scattered about in all directions and was concerned that the waning light was going to make it difficult to locate them. I took my Oregon Pack and placed it on top of the sagebrush I had been sitting in and dropped the fluorescent orange panel down. By using the orange panel as my reference point I was able to quickly locate all four coyotes. What had started out as a slow day ended in a fast and furious finale.

Comments will be approved before showing up.

A. Chest

B. Sleeve

C. Waist

D. Inseam